Considering the startling installments through which we’ve lived, surely you’ll pause when I tell you that while tossing a bag of aluminum cans into a recycle bin, I saw a ghost. In a moment of transparency, I perked up to the nearby grassy green of my 7th grade English grammar class not far from the concrete pad on which I stood. The grand and now defunct Whitthorne Junior High School building assembled like a phantom before me.

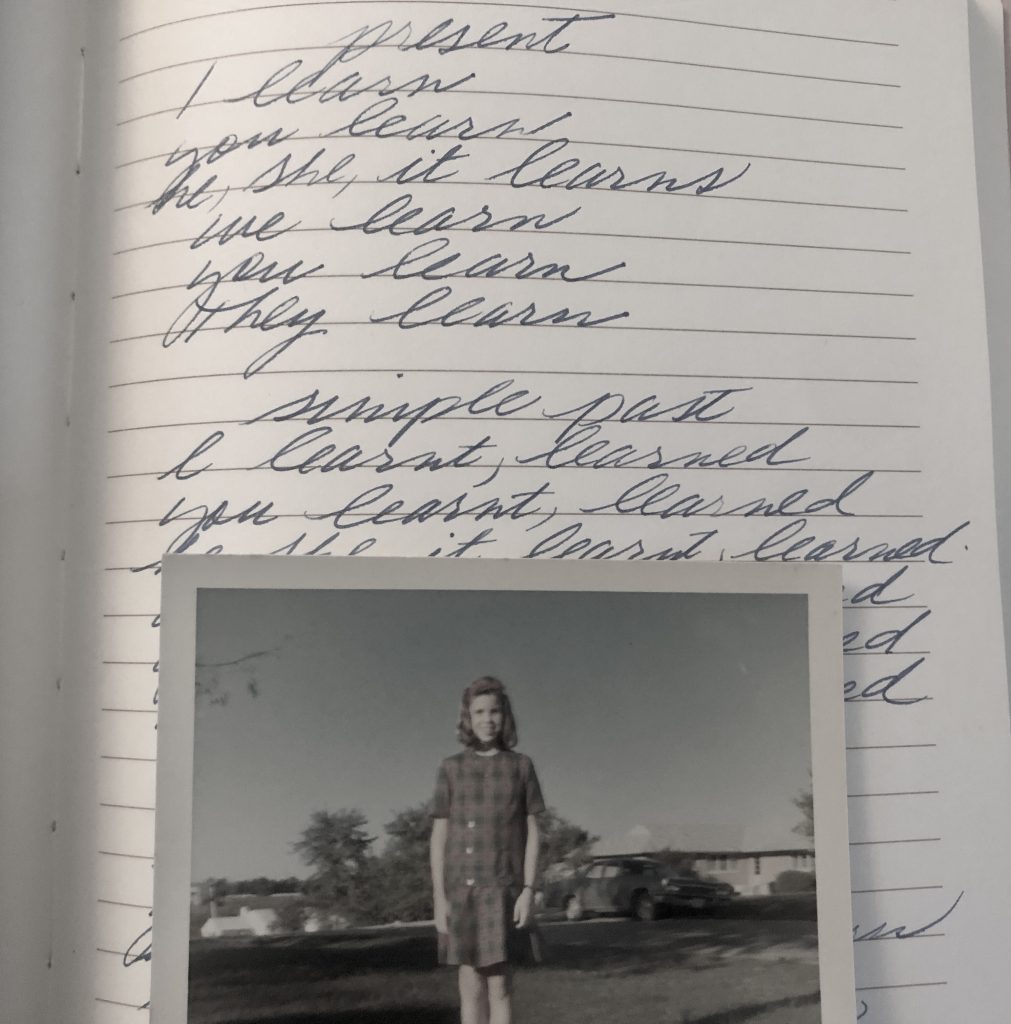

It’s not an overstatement to say that though the drama of that space is ancient history, first period class under the sway of Mrs. Marjorie Haynes in 1967 is vividly imprinted by way of my expectancy and her expectations.

Rites of passage like switching classrooms every hour and walking to the drugstore after school opened breathers where we would give our budding personalities a ride. Still when I saw Mrs. Haynes on my class schedule card, I knew that I was in for it. We all did. Her persona preceded her; besides those were the days when students were subservient and teachers were martinets.

As I gazed at the apparition of a long and airless hallway from my perch fifty years later, I saw the petite bristle of Mrs. Haynes standing guard at the classroom door greeting us one by one with a cursory nod.

Arms crossed atop her perfectly altered grey suit, jacket buttoned almost to the top with a bit of blouse bow peeking through, she was the picture of dignified wariness. I cannot say that she ever truly smiled, but her tiny straight teeth were generally bared, and her eyes were pulled tautly by the effervescence of her eternal bun. Her black high healed Oxfords were shiny and laced with a double knot.

As the old southern idiom goes – she was tighter than Dick’s hatband as we filed in and took our seats at individual desks arranged to demonstrate the military precision of a weekday work detail. We settled in to what would prove to be an anxious hour of dry mouth.

I strangely loved it and her though I once almost fainted while diagramming a particularly complicated sentence while standing in front of the class, my voice cracking with uncertainty. The mix of chalk dust motes and sunlight streaming through giant windows, the whir of stainless steel pedestal fans and the snap of her interrogation combined to reflect an Alfred Hitchcock film. Where would it end? Would it damage our confidence or propel our ability to play the game?

All I know holding the bag here decades later is that I never again learned anything in the realm of English grammar or proper sentence structure more long lasting than within the daily grind of Mrs. Haynes’s class.

As time passed, her sense of humor bloomed into moods of creativity. We all took turns in the production of bulletin boards: my friend Sue and I were jazzed to design and assemble the story of Pandora’s box. She prompted us all to tryout for the school newspaper The Junior High Jots.

With my first published piece: The Contemptuous Combination which detailed my difficulties with locker maintenance, she celebrated possible futures. She became more congenial as final verbs were conjugated.

Even so she was a stern taskmaster to those who were squirrelly with the rules, particularly Vernon who had been made to repeat her class. Memorization assignments ring in my ears especially Abou Ben Adhem by Leigh Hunt which I can still recite today. I like to say – stamped in fear but retained in joy. Reading aloud was required each day, a pressurized but necessary part of “having voice.”

I called her to mind many times in the ensuing years. Once I dropped in on her tiny but immaculate house. She was invited to our wedding and promptly acknowledged the occasion with a gift and monogrammed note of regret. Social forays may not have been to her liking as I recalled the way she stood apart from other teachers. Was she setting a standard or sorting out a shyness?

Sometime in the mid 1980s, I was at Kroger and noticed in the refrigerated section a dainty version of hell on wheels. The silhouette commanded a second look. Before me stood a vision with long fine white hair, black jeans and leather jacket, black high top tennis shoes and a bit of tee shirt logo peeking through which I was too timid to read.

“Mrs. Haynes!” I said with an earned tremble, “You have a new look.” While holding an armload of groceries within earshot of busy shoppers, she pulled me closer to the cold air and spilled it.

She and her husband of a lifetime had retired and were about to celebrate with a European vacation when he died suddenly. With this stunning revelation, I wobbled in my shoes. The unbuttoning of who I had known Mrs. Haynes to be was staggering.

And still she continued: “I found a therapist who warned me if I didn’t loosen my bun, I too would die.” Challenging as it was, I looked into her eyes. And then she said, “The therapist suggested that I find my first true love, the one my parents would not allow me to marry.” Her voice broke.

She revealed the story of their new found blessed relationship and then she looked down at the ground. He died not too long ago,” she said.

I gave her a hug, and we continued the rehash of her rebirth all the way through the checkout line. I thanked her with a tale about a college professor who read my essay of merit out loud to the class. “You made that possible,” I said.

Her eyes went vague. Mrs. Haynes was no longer there; Marjorie was enmeshed in the agency of aging and had moved on.

That was the last time I saw her. A while later, I read her unremarkable obit per current day journalism – just the facts, none of the heart. And so, I speak of her significance: Marjorie Haynes gave every iota of her intellectually prone being to her profession. Within a dedicated life, she suffered from many things that did not pay off in ways that she imagined.

She was often a stranger to herself and others. Nevertheless as in the mimeographed worksheets she handed down the rows of desks, there was much work to be done – vital answers to be composed and self expression through the written word to be practiced.

In truth I realized while on a trip to Paris that she had in fact recycled me. She materialized at Jim Morrison’s tomb in Pere Lachaise Cemetery where the epitaph reads – “Faithful to his own spirit.” Majorie Haynes showed the way; the rest was up to her pupils.