The two drawers at the bottom of their secretary were inventions of time well spent. Not one of the cousins could resist the eventual examination of what was inside.

Filled to the brim with photographs, primarily black and white, the drawers were removed during each visit for closer inspection. Some photos were creased and torn and others yellowed, each one haunting in its own interpretation of events. Some pictures were documented on the back, but just as many remained nameless, dateless mysteries.

In winter we would dump the contents onto the mauve woolen carpet in front of glowing ceramic coils. In the summer, we’d take them to the wooden floor of the screen porch and make up stories about unknown faces as we shuffled some and fanned ourselves with others.

They were a jumble of the Illinois Griffiths and the Kentucky Quinns. For the years traversed, the photos were limited in number for these were rigid days of studio portraits and staged celebratory freeze frames. Fewer snapshots were taken, but most all were printed to make up this parade of unsmiling faces. Family lore explained that a great grandmother flattered my mother’s engagement picture with “Well, I’m thankful she has the dignity not to grin.”

The Griffith side was far from equally accounted for, and we children were unattended as we read between the lines. Clearly my Grandmother (Quinn) was uninterested in my grandfather’s people. When I asked her about that side of the family, she curtly said, “Dr. Griffith was a darling little man.”

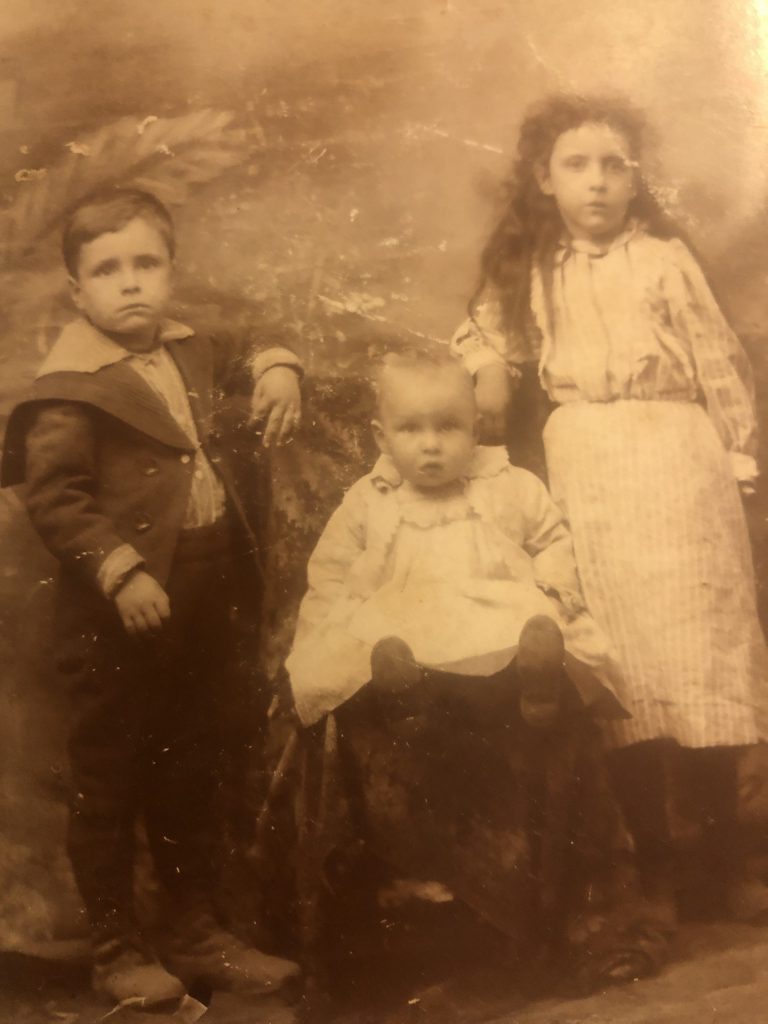

My grandfather Claude Madison Griffith (CM) is the earnest little fellow with the double-breasted coat. He looks like he might have an inkling of what is in store beginning with the duty at hand, a portrait for his mother Esther. I did not recognize him in the conglomeration of Sepia Tone photos until later when my Mother pointed to his familiar eyes and called out his sister Goldie and brother Lenniel.

Little Claude was born in the sparsely populated Hardin County, Illinois to a beloved rural doctor. Dr. Alamandor Stratton Griffith’s obituary testified to the value of his presence among the people he served. During the week of CM’s birth, President William McKinley, a major in the Union Army, was president and the U.S. raised a flag in Puerto Rico. This context is noteworthy because Grandaddy was forever an eager beaver news reader. His opinions were guided by character or lack thereof.

He would often speak about his time in a one room school house with 73 students of all ages. The room had an outside privy and a wood burning stove. Winter was for ice hockey, and summer was for baseball.

At 12 he bought 2 calves for 10 dollars a piece and raised them until he had 74 head by age 16. While driving his father by wagon on house calls, he surmised that most illnesses were mental and proved his point by never going to the doctor or taking even an aspirin for relief.

Without the consent of his parents, he took a temporary job with the Northwestern Yeast Company and traveled by train to retailers. He saw the country and set ablaze a lustful curiosity. Enroute he observed that people had only awareness of their own communities.

After a stint as a teacher, he enrolled in Palmer’s Chiropractic School in Iowa. His goal was to practice with his father and create a unique standard of care.

While in school he attended large events every Friday night sparking the enjoyment of rollicking bands and dancing crowds. By 1913, he had moved his practice to Henderson, Kentucky where he met my schoolteacher grandmother, not at a dance but at church.

CM pitched into the community with zest, and he prospered. After an early morning wedding, he and my grandmother got a friend to hold the ferry to cross the Ohio River. A new 1800 Studebaker coupe would deliver them on a long road trip to Niagara Falls.

With a substantial net worth by age 32, CM heard tell that the same properties were selling 3 times in one month in the rustic state of Florida. With a son and daughter in tow, he and my Grandmother gambled their security in the wilds of Ft. Lauderdale. He opened Fort Lauderdale Abstract and Title Company to a first year’s successful profit of 50,000 dollars.

After the hurricane of 1926 and a land boom collapse, they lost it all. The Griffiths set their affairs in order and paid their debts. The time had come to begin again.

He borrowed 100 dollars from his brother-in law and took the bus to Memphis for a job stocking shelves. Banks were closing. Out of touch with his family still in Florida, his son-in-law later wrote about him, “CM stood apart as he put one foot in front of another and formulated a watchful and patient stance in search of opportunity.”

Though he had never seen a black person until his twenties, while in Memphis on a walk to work each day, he developed a deep empathy for the lack of opportunity and freedoms that living on the outside created. This would later compel him to refuse participation in the White Citizen’s Council while living in the Mississippi Delta. He said, “I could never hold back anyone who wanted to improve themselves. They should have every right that I do.”

He followed up on an ad in the Commercial Appeal to lease a hotel in Marks, Mississippi. It was there that he and my grandmother were reunited resulting in the birth of my mother. Just in time, a career comeback was underway in hotel and restaurant management. He and Margaret worked round the clock for years running the Lamar Hotel in Yazoo City, Mississippi and then the Burton Hotel in Danville, Virginia.

Brisk wartime business took a toll on family relations and caused trembling but their son survived as a paratrooper in the Battle of the Bulge. Later C.M. made attempts to financially redirect his son into the favored sideline business of cattle but to no avail. The two would become estranged.

In retirement he served on the board of the First Land Bank in Mississippi where he was responsible for loaning money to farmers at low interest rates. The Griffiths adopted the deep values of simple living and stopped work early to focus on their 9 grandchildren. They spent half the year in Tucson as a remedy for my grandmother’s arthritis.

Immediately after Margaret’s death, CM was surprised to find his own joints crippling with arthritis, but remained independent with the help of his youngest child, my mother. He lived out his days in Columbia, Tennessee. When my mother died suddenly, he had a stroke and died within a year.

Though inconsistencies created by spiritual growth seem to have caused some family strife, he strove to help others both black and white to attain financial independence and gave without ceasing to The Salvation Army.

My cousin Charlie remembers the grandfather of our childhood as a man of few words, but generous with his time for all cousins. Most of us stayed with them in their Yazoo City home for frequent visits where we walked to town every morning, visited the library, worked in the “cultivated rain forest of their garden” and played, as Charlie said, in “the amazing otherworldliness of the canal in the middle of Canal Street.”

Indoor breaks revolved around games of Password, Go Fish, the Ouija Board and dress up. Naps were a daily-given along with folding clothes and meal time within “the heat and steam of an endless queue of pots, pans and chatter” – (thank you, Charlie)

Touring the nearby Vicksburg Battlefield was on the calendar with its steep bluffs, river views and equal time for US troops and Southern rebels. Grandaddy was keen on the story of this setback.

He and my grandmother took each grandchild on a memorable trip somewhere in the country. If nothing else, they stood for broadening our horizons.

Throughout the trials of his almost 100 years, the Bible thumping righteousness of his elders’ formula gave way to exercises in empathy and he stopped attending church. He read endlessly about culture and religion. His focus was revealed in the belief that thoughts were Herculean things. Science of the Mind by Ernest Holmes best explained his conclusion.

Until the end he smiled. Once I found him alone in the dark with his head bent in prayer while massaging his twisted hands. In my discomfort for him I said, “Grandaddy are you alright?” He said, “There are so many wonderful things to think about.”

During this time of upheaval, I am galvanized by the challenging life events that CM met with resilience, and I smile too. His determination and faith never allowed for despair. He comes to me often in his non-physical body and tells me like it is.